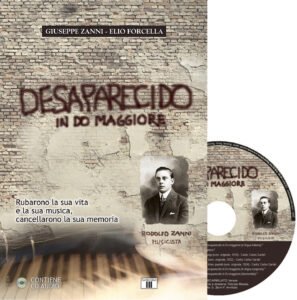

The Life

Rodolfo Zanni: an «Argentine Mozart »?

by Giuseppe Zanni

On September 16, 1922, at the Colon Theatre of Buenos Aires, the playbill announces, for that evening, a Grand Symphonic Concert, remembered in the annals as an extraordinary event that consecrated a young Argentinian musician, the son of Italian immigrants.

Rodolfo Zanni, the composer and pianist, is only 20 years old: in front of him is an orchestra of 120 players and 100 choristers. The program for the evening is completely made up of works written by him; he is conducting in honour of the President of the Argentinian Republic, Torcuato de Alvear and his charming wife, the soprano Regina Pacini. The evening is exceptional, it has been publicized relentlessly for many days before and the reviews will talk about it for many days after: they tell of the success of the young and illustrious maestro, acclaimed by the public, but there are also criticisms and bad reviews that, by their very ferocity, reveal an aversion for, and an envy of, his success. It seems the start of a distinguished career; one would normally expect it to continue at the highest levels, and for him to frequent the country’s most important theatres and concert halls and beyond. But nothing happens. After that day, a thick curtain of silence falls on Zanni, a curtain which undoes the event, ignores it, deletes it, relegating the once much acclaimed artist to anonymity.

He is buried in the cemetery of San Jeronimo, in unconsecrated ground: only a few years later, his remains are exhumed by persons unknown, and taken nobody knows where. His body cannot be found. And there is no trace of his hundred or so compositions including symphonic poems, symphonies, ballets, sonatas and two operas: Glyceria (with his own libretto) and Rosmunda (with a libretto by Sem Benelli).

But who was Rodolfo Zanni? ‘‘Sonidos Argentinos’’ paid homage to him, upon the bicentennial of the Nation, defining him as one of the most enigmatic and fascinating figures of the country’s history, and asking whether he was « an Argentinian Mozart? », adding that « very few musicians or music lovers will admit to having heard of this artist whose precocious talent lit up music audiences in Argentina and neighbouring countries at the beginning of the twentieth century’’. He lived for just 26 years (the same number as Pergolesi, nine less than Mozart and five less than Schubert) and his talent was so dazzling that he drew the attention of a legendary European conductor: Felix Weingartner (1863- 1942), one of Liszt’s favourite pupils. We know that Rodolfo was born in 1901, in Buenos Aires, to Italian parents emigrated to Argentina. His father Nicola came from a town in Abruzzo, Atri in the province of Teramo: he recorded Rodolfo’s birth at the registry office – as his natural son, born of a woman who did not wish to be named. Teresa Vitale the mother who would recognize Rodolfo as her son only later, was originally from Genoa is thirty years old and still unmarried. Eleven years earlier she had had a daughter, Fernanda, also not recognized at birth, either by her mother or her father. The connection with Italy would have remained unknown had very recently fortunate coincidences not led to the discovery of an official document in which it is certified that Mr Nicola Zanni, Rodolfo’s father, was born « en el pueblo de Atri, Teramo » and that he had been resident in Argentina for 42 years. The town of Atri has recently paid homage to its son by means of a large public ceremony attended by the mayor Gabriele Astolfi and by the head of cultural events Domenico Felicione, together with the ambassador of Argentina in Italy, Torcuato Di Tella, a former Culture Minister of his country, and in the presence of two world-famous singers: Daniela Dessi and Fabio Armiliato. A street, in his town of origin, Atri, has since been dedicated to Rodolfo

Zanni.

Although we can now trace Rodolfo Zanni’s genealogy, little is known about his life and childhood. The scant information we have paints him as a child prodigy, a brilliant adolescent, a talented musician from a very early age.

He was only 9 years old when he deposited some of his songs for voice and piano in the National Archives; that have now been found, including one called ‘‘A mother’s affection’’; he is 14 years old when receives his diploma as a Master of Music from the «La Prensa» Music Academy, winning first prize, as well as the only gold medal awarded by the Institute. He is granted a scholarship by Alberto Williams, an important musician of the period, who takes care to supervise his studies of harmony and counterpoint. But the young musician wants to proceed expeditiously: he forges ahead in his studies and soon leaves his teacher, deciding instead to teach himself. At the age of 16 Zanni conducts a large orchestra presenting the most significant works of the Italian lyrical repertoire together with his own compositions in a tourn through Chile and

Peru: the success is enormous, as is the praise from the press. He meets Mascagni and Weingartner, who recognise his talent and praise him in autographed dedications.

Then, in 1922, Weingartner chooses him for his Wagner program, appointing him as the preparatory maestro and stage director for Wagner’s ‘‘Ring Cycle’’, a notoriously difficult work, but Rodolfo earns unanimous acclaim. Again in1922, he is selected to form part of the roster of the Colon’s conductors and he conducts the Concert already mentioned above on September 16th.

What happened? Many factors contributed to the ostracism of the talented musician,

first of all, his way of being, his personality. The young Zanni had a well-defined character; he acted decisively and uncompromisingly. He had an innate tendency to clash with authority, albeit without premeditation or arrogance. All his actions and even his music show him to have been a person who adopted different ideas and positions from to those of his contemporaries, a heretic within his musical community. He dissents from the dominant opinions and rules of the establishment, rejecting the existing hiererachies. His triumph before Argentina’s President was deemed provocative, and certainly perceived as an affront, arousing the uncontained envy of the mediocre but influential figures that he had neglected. It is also possible for us reasonably to suppose a friendship how intimate it is not given to us to know with the first lady, the soprano Regina Pacini, which would explain, at least in part, the extraordinary opportunity he was given to perform a program of only his works in the most important theatre of the country. Last but not least, his situation was aggravated by the looming presence of the ‘‘Liga Patriotica Argentina’’. This was a extreme-right-wing or-ganization, created in 1919, which had a political wing (its founder Domecq Garcya was a member of De Alvear’s government) and a paramilitary wing: they operated across the country, via various brigades and squads. Their actions were at the limits of criminality, against anyone who was different: the heretics and the impure that offended Argentine nationalism in all areas of society, including the arts. We have an amazing account from Mascagni regarding the strongly anti-Italian climate in the musical world of Buenos Aires: he tells us of the harassment to which he himself was subjected. But for other less well-known and defenceless artists, the treatment they received was surely more brutal: scholars of the period wrote that the brigades attacked «undesirables» with an iron fist, even going so far as to murder them. They took possession of their property, made their bodies and their works disappear. It is a dark time in the history of Argentina, which has yet to be sufficiently investigated. The presence of the ‘‘Liga patriotica’’ casts a sinister light of suspicion also on Rodolfo’s death. The persecution. Emilio Pelaia explained everything in an unambiguous article published in the journal « Disonancias’ in January 1928, immediately after Rodolfo’s death.

Cinema, radio, tango.

Before his death, Rodolfo was persecuted by his enemies, who had closed down every opportunity for him to work in his field; he had therefore devoted himself to scoring silent movies, again earning enormous and sincere praise for his efforts. We must not think of him as a musician busking in delapidated provincial cinemas: he composed real music to fit in with the film and personally conducted an orchestra of 20 musicians, obtaining a great success. At the Real Cine Theatre in Cordoba, thousands of people (3008, to be precise), went to the cinema to listen to his music, as shown by the playbill of the movie ‘‘Vagabundo de amor’’ that we have rediscovered: there Rodolfo’s name is as prominent as that of John Barrymore, the famous Hollywood actor! This extraordinary capacity he had for adapting to circumstances made him work also for the radio, which in those years was establishing itself in Buenos Aires and throughout Argentina: that was an extraordinary way to be heard and judged. Soon he found himself at the piano performing pieces by Wagner, Grieg and Debussy, but also his own compositions, such as ‘‘La Fiesta de la aldea’’, ‘‘Nerone’’ and the ballet ‘‘Las Ninphas’’. He was brilliant even in recognizing the potential of new means of musical expression; he immediately understood the value of the tango. He was only seventeen when he gave a favourable opinion on it. Rodolfo also worked competently and authoritatively as a music critic in publications such as Orfeo, Critica and

El orden.

His works.

Zanni’s musical output is unfortunately missing. None of his 81 works, whose titles we largely know from Arizaga’s reconstruction, has survived. There is no trace either of his symphonies, ballets, sonatas and overtures, as well as his lyrical works such as ‘‘Glyceria’’ and ‘‘Rosamunda’’. Searches in the national archives, where it is certain that his youthful compositions were deposited, and in the archives of the Colon Theater have not produced any results. It is also impossible to find his symphony ‘‘Las Ruinas de Jerico’’ that the Deliberative Council of Buenos Aires purchased for the far from meagre sum of 2,400 Argentinian pesos! It all sounds incredible, yet the research of skilled musicologists (including Argentinians: one of these is Maestro Lucio Bruno Videla), who have spent many years investigating in libraries, private collections and public archives devoted to collecting the music of that periodhave all proved fruitless. They have not clarified anything but, on the contrary, have served to feed our worries and suspicions. Rodolfo’s direct niece, his sister’s daughter, was traced and asked questions about the fate of her uncle Rodolfo’s musical production: her answers were evasive and negative. She finally told us that her

uncle’s works were all destroyed, butshe refused to say how this could have happened, claiming to know nothing. In the mystery of Rodolfo’s life, already so intricate, there is another puzzle: the « mystery » of ‘‘Rosmunda’’, which we mention here briefly. We know for sure that in 1922 Rodolfo had already completed the score of the opera to a libretto by Sem Benelli; Foppa, a prestigious contributor to the « Diary of the Plata », writes on September 5, 1922 writes that « his [Zanni’’s] latest work is Rosmunda, a tragedy in four acts by Sem Benelli, published by Ricordi of Milan and that is going to be put on stage next season in Italy. » This is confirmed also by the testimony of Pelaia who speaks about it as someone who had direct knowledge of the work, writing that « only those who have had the opportunity to read through the score of his Rosmunda can appreciate the quality of the musician at its true value’’. And then we have a further confirmation from the Colon’s official magazine of 1972, in which we find reportedthe testimony of an opera impresario who says he knew for a fact that maestro Zanni had finished orchestrating his ‘‘Rosmunda’’ and also that Nicola, his father, insistently asked the management of the theater to stage the work of his son after the latter’s death.

Well, the searches carried out at the publisher Ricordi have not produced any results, neither at its headquarters in Milan, nor in its Buenos Aires office, where some of Rodolfo’s arrangements are deposited, but strangely, none of his compositions. In short, a fascinating and complex history, much more of which will be told in a biography, currently in preparation.